My latest Wired column came out — and this one is about a new trend in 3D printers: Using them as thinking tools. It’s online here, and a copy is below …

Meet the neurosurgeon who uses a 3D printer before operating

by Clive Thompson

Ed Smith does some fiendishly difficult surgeries. A paediatric neurosurgeon at Boston Children’s Hospital, he often removes tumours and blood vessels that have grown in gnarled, tangled shapes. “It’s defusing-a-bomb-type surgery,” he says.

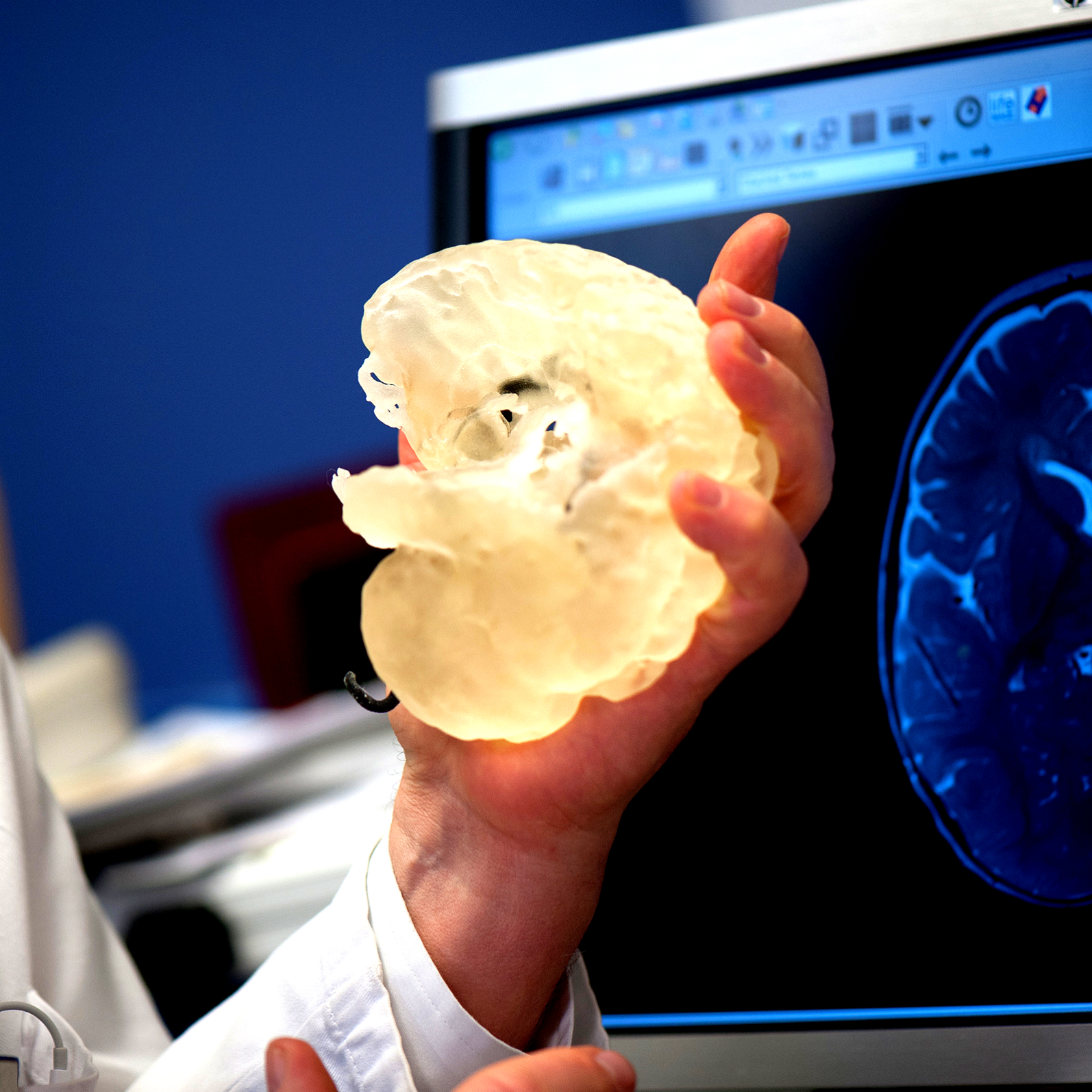

So these days, Smith prepares for his work by using an unusual tool: a 3D printer. Days in advance, hospital technicians use standard imaging to print a high-resolution copy of the child’s brain, tumour and all. Smith will examine it for hours, slowly developing a nuanced, tactile feel for the challenge. “I can hold the problem in my hand,” Smith says. “I can rehearse the surgery as many times as I want.” During the operation, Smith keeps the printed brain next to him for reference. As a visualisation tool, it’s so powerful that it has reduced the length of his surgeries by an average of 12 per cent.

Smith’s work will make you look at 3D printers in a new way. Most of the time, they’re pitched as tiny artisanal factories, useful for cranking out one-off products and niche objects: a desktop-sized industrial revolution. But what if it’s more? What if the 3D printers are going to be equally useful — or even more so — as thinking tools?

The 3D printer’s intellectual impact is going to be like that of the inkjet printer. We (correctly) do not regard printers as replacements for industrial presses. Few people print a whole newspaper or book. We use printers as cognitive aids. We print documents so we can array them on our desks, ponder them and show them to other people. That’s exactly how Smith uses his 3D printer. He doesn’t print the brain so he can have a product. He prints the way you’d print an email — as a document, yes, but more as a way to understand data and solve problems.

Doctors have long used MRIs and CT scans to help visualise tumours. But when the visualisation is physical, it has a haptic impact that screens do not. That’s why architects build scale models of their buildings: only by peering around a structure do you “get” what’s going on. “You see these spatial relations and depth of field that aren’t possible on-screen,” Smith says.

It works for more than brains. Last winter, Nasa astronomers printed a model of a binary-star system to help visualise its solar winds. “We discovered a number of things we hadn’t fully appreciated,” says Thomas Madura, a Nasa visiting scientist. 3D prints are also great for accessibility, giving the blind a new way to grasp astronomy. (Maths, too: an enterprising San Diego father printed fractions so his blind daughter could learn them.)

To really unlock the power of 3D printers, the tech will have to improve. If we’re going to use physical “documents” the way we use paper ones – glancing at them for a moment, then tossing them aside – we’ll need material to be recyclable, even biodegradable. Imagine the 3D printing equivalent of a Post-it note. What’s more, we need our intellectual culture to evolve. We don’t value or teach spatial reasoning enough; “literacy” generally only means writing and reading.

There can be all sorts of uses for 3D data. Courts could print forensic evidence that juries could handle. You could render a sales report as a sculpture. 3D printers aren’t just factories for products — they’re factories for thought.